Richard Branson: Abolishing the death penalty

One area of particular concern to death penalty opponents like me is the so-called war on drugs. At least 32 countries still prescribe the death penalty for various drug offences. […]

One of these countries is Iran, which has in recent years seen a dramatic increase in drug-related death sentences and may execute more drug offenders than any other country in the world – over 300 people in 2014 alone. Most recently, Indonesia executed six drug offenders and plans to execute more – including the Australian leaders of the group known as the “Bali Nine†– in the coming weeks.

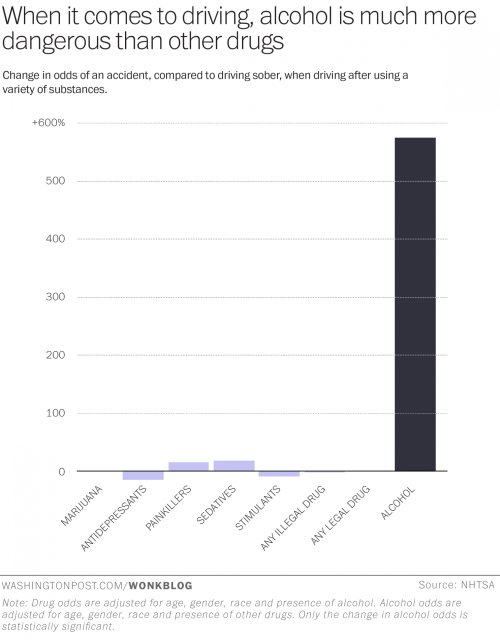

Both countries claim that executions are an important and effective deterrent. Nothing could be further from the truth. Drug use is a daily reality in Iran and Indonesia, with a dramatic increase in the illicit drug market observable especially in Indonesia. Tough law enforcement and draconian sentences, including executions, have failed entirely to change this status quo. Overall, there is no scientific evidence to support the claim that the death penalty has a deterrent effect on those using and trafficking drugs.

Like Branson, I am opposed to the death penalty in general, for a variety of practical and moral reasons. And to use it as a tool of prohibition seems somehow even more heinous, given the destruction caused by prohibition.

It’s an additional reason to push for legal regulation of drugs, and in the meantime, at the very least, we need to stop incentivizing it — which is what happens when we provide financial assistance to these countries for their drug war.