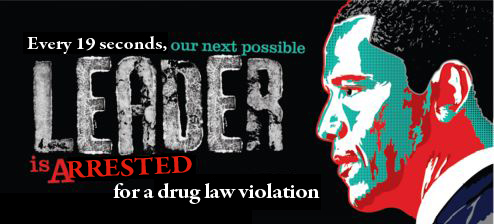

This one is from Medaille College in Buffalo, New York, where Chris Ripley, Photo Editor has an OpEd titled Legalization would be a detriment to our society: Should New York state dance with ‘Mary Jane?’

Cute subhead, Chris. I don’t think the media’s ever thought of using ‘Mary Jane’ that way, before.

Compelling writing usually begins in the first sentence, and this one doesn’t disappoint:

As I was thinking about what to write for this article, I only knew what was bad about this drug and that it is not good for you. When I was growing up my parents always told me: ‘do not do drugs and never talk to strangers,’ and to this day I really don’t do either.

But wait…. I’m a stranger…

My mother told me stories about people she knew that did drugs and that their lives were severely effected by the use of them. Drugs harm your body as well as makes you do things that you are not suppose to do. I always believed this because my mother is a very convincing person and what she said was the law when I was younger. So basically fear is what makes me not do drugs.

I checked — Medaille College does have an English major with actual faculty. I assume at some point, they discuss things like grammar. Apparently young Chris hasn’t experienced that yet. He has experienced fear, however, from his mother. Apparently, however, the rest of the student body had different mothers.

As I entered college, things like sex, drugs, and alcohol became very easy to come by and take part in.

And now we have learned a rather disturbing fact about the lack of discrimination on the part of the Medaille women.

I know people that smoke marijuana and I have seen people smoke it, but what I do not understand is the reasoning behind why they want to do it.

Me being a person that questions a lot about life [with the apparent exception of what his mother tells him], I asked people what it was like and why they do it. The answers I get are all the same. They say, “It makes me feel good, and it helps me relax,’ or ‘It helps me calm down and take me away from here.’

Well that sounds like a vacation to me, and a very dirty vacation. If I wanted to go somewhere that was relaxing and calms me down, I wouldn’t choose marijuana.

Ah, but you can’t go to the Bahamas every Friday night. In fact, in Buffalo, New York in the winter, there aren’t too many places to go to relax and calm down. Plus, marijuana is cheaper than taking a trip.

He goes on to talk about the tar in smoke, and then notes:

I have many allergies and have asthma, I feel like smoking would just cause me more of problem then that great feeling that you get if you were to take a hit. Or maybe it is just the fear of something bad happening to me that I cannot control.

Well, then, Chris. It seems very clear that you should not smoke marijuana. You aren’t interested in it, you don’t like smoke, and you’re afraid of your mother.

Some other people, however, are interested in it, don’t mind smoke, and aren’t afraid of your mother.

So back to the point of why I am telling you my opinion on smoking marijuana. Well, America is at a point that people are fighting for the legalization of marijuana. If you haven’t figured out by now, I think it is a very foolhardy idea to legalize marijuana.

You may think that, but you haven’t given a single reason why. And you haven’t begun to touch on the costs of prohibition or any actual benefits from keeping it illegal.

We as a nation cannot handle this drug,

No, you as an individual can’t handle this drug.

… and it would be very detrimental to us as a nation.

Why? For what reasons?

If you really want to have a good time, keep it off the streets and don’t smoke marijuana.

I’m not sure I want to take Chris’ suggestions for calming vacations if his idea of a good time is “keeping it off the streets.”